Peter Post

I’m not there – Bob Dylan and I

(2015)

(German original of the essay)

As a postwar child in an Americanized Germany, I first came into contact with Bob Dylan in the year 1976. I remember when one of my buddies, inspired by Hurricane, recited it to me using pantomime. I don’ know anymore if I heard it myself. I remember how this buddy was amused by another Dylan song and liked to quote it and in German, namely: “Every time an idiot wind blows just when you open your mouth.”

The next thing I remember in regard to Bob Dylan was when I was privately at the home of my lady Internet supervisor. She had the chronological next record Street Legal; we played it to coffee and cake. The dark-silver mood of this recording impressed me.

In 1980, I was compelled to move to southern France. In a marketplace café I heard Gotta Serve Somebody on the jukebox. I found that very notable; I hadn’t the slightest idea of what was to come.

I heard back then – with a view over the rooftops of Montpellier, the Mistral wind blowing – most of the time Rust Live by Neil Young, but Bob Dylan belonged to those artists who made me listen up and who meant something to me.

*

Later this year, 1980, the moment was reached. I had moved again up north to Paris. I drove quite frequently to Beaubourg, where I could listen to the latest LP recordings on the left side of the ground floor. One day I had the lady disc jockey put on the latest Bob Dylan record – and then it happened to me.

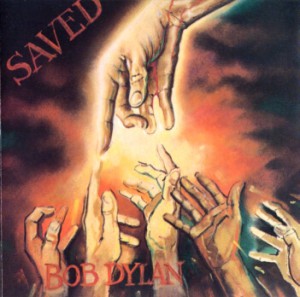

From then on for weeks on end, I was in the Pompidou Centre every day to listen to this record – Saved – sometimes even twice in a row. I was so delighted, so fascinated, with this recording that I can barely describe it. I remember forever the exact surroundings around me: the bad air in the library, the dirty yellow foam rubber of the headset – how gladly I wish I could sit there once again today… I don’t know, I always slipped several floors deeper in my soul, when I listened to these songs; it was as if they were utterances of my own soul. I was one with this record. Maybe Saved saved my life.

Many music critics tore Saved apart. I always asked myself: just what do they hear? Do they feel anything at all? How could they write such rubbish about this music? It was always singled out and shoved into the foreground that Dylan had converted to the Christian faith and was now a religious zealot or something similar. That or something ideational or conceptual at all – how could this play a big role in their critiques? Couldn’t they perceive that someone was expressing himself in an extremely personal way?

Today, I think that these journalists reacted back then for whatever reasons like Pavlov’s dogs: it was just senseless reflexes, which were triggered by some breaking of a taboo. Today, this sort of severe aversion on account of an artist’s leanings toward Christian religiosity is no longer comprehensible – today there are other taboos and hysterias.

When I immersed myself deeper into this music, I naturally didn’t think of journalists. But I’m still astounded several decades later, when I was able to watch concerts from this era in the Internet. And, in fact, since I was able to perceive, looking back, a very clear contrast in the reactions of the fans in the concerts, which then still surprised me; the public accepted by no means the most destructive – partly even mocking – criticism of the so-called Christian albums: Slow Train Coming, Saved and Shot of Love.

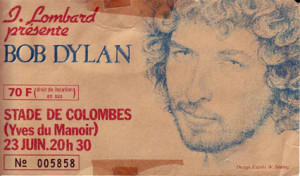

For me, they were not only Dylan’s best records – his concerts at this time are the best (next to those of the Hard Rain-phase), which he ever held. (The concert which I attended myself in 1981 did not approach this quality – probably due to the conditions in the football stadium.) When one sees what kind of fire the band and the female singers ignited and how the public enthusiastically went along, then the very different perceptions by the critics and by the public becomes apparent. I don’t believe that the ideational played a big role with the public: it was just swept along by the seriousness and solemnity – the fans felt that they experienced a very special opening, a sort of revelation.

*

I am not at all religious. If one wants, I’m an agnostic; that is, I’m not interested in the question whether God exists or not. But these “religious” Dylan records do indeed play a role, in fact, a very big role in my life. They speak to me in a very emotional way. To see a contradiction here does not interest me further.

It’s remarkable, however, that another music, which had a similar influence on me, likewise has a Christian religious origin: that of Johann Sebastian Bach. (The quasi-non-religious Richard Wagner I discovered two years ago.) It is fantastic music; one asks oneself how a human being could create such compositions. Even here it is pure fascination – only derived from feelings.

After the Saved experience, I bought all the Dylan recordings: older ones and the recent productions included. I became a genuine Dylan fan and was quite versed with Dylan’s entire song inventory, not just the Christian ones.

I also bought all available Dylan songbooks. I had a job as lifeguard on Corsica and sat there the whole day on the beach and played all day long from the songbooks of Slow Train Coming and Saved. Thank God there were no accidents or drowning.

In the evenings the jukeboxes played John Lennon’s beautiful songs Woman and Watching the Wheels in the bars.

On the way home then at the airport in Ajaccio, I suddenly saw from the bus the new Dylan record in a display window: Shot of Love – the cover glared back at me, and I could hardly wait to buy the record in Paris.

Two years later, in 1983, I see myself standing in line in a cultural shop holding the album Infidels in my hands, which was heralded as the end of the Christian phase…

*

If one becomes familiar with the work of an artist in such a way, than all possible aspects of the confrontation with these works come into the foreground and the translations of his texts as well: first just content-wise, then also formally: one tries to find ways to bring them into German verse. It is quite common that lyricists like to transfer the poems of lyricists of other countries into their mother tongue.

Bringing over song texts into one’s own language and putting this into verse in only one form of dealing with the work – it simply follows, forces itself, is fun. It is something playful; one enjoys experimenting with language – it belongs to it somehow, if one loves works of art which consist of text.

I’m a lover of the art of Dylan; it belongs to such a hobby to interpret the songs one’s self. Naturally, I’ve sung all the songs, myself, since way back, on the guitar. For a public release of various cover versions with original texts, there was no impelling reason. But I regard it as justified to add my own adaptations to a substantial number of German interpretations. Previously there was little middle and late Dylan but much more of the early Dylan at the center of interest of German interpreters. I often had to think over the German versions of Dylan’s lines: “You think he’s just an errand boy to satisfy your wandering desires”.

In the end, this work is also a sort of appreciation and appropriation of US-American culture. Under other conditions, we might have concerned ourselves perhaps with Chinese artists and might have sung and translated Chinese songs. Every era of military and cultural dominance comes ultimately to its end; then one again remember one’s own – or subjugates one’s self to the next. The US-era now – „you better start swimmin‘“ – passes; an honorable departure takes place – how otherwise than with German versions of songs of the most important living artist of the USA?

*

For me – what one might imagine – the texts of Dylan don’t stand at the focal point; and I don’t belong to the Dylanologists. For me, the music is also not the central issue. What is then the main issue with Dylan?

It consists of the previously mentioned fascination, which naturally includes all the other creative periods as well, not merely the “Christian”. It’s related to a certain attitude. Others of his works naturally also testify to this said seriousness and great personal concern. There is simply no other artist in popular music – with the exception of Leonard Cohen – who extracts from the contents of his most inward soul as does Dylan.

The atmosphere in Dylan’s art is characterized by a high degree of authenticity. Here lies its fascination. It derives from his creativity and expresses this. I can see nothing closed or mystifying – his work is a revelation. In that which he does – with whatever symbolism he may work with – he is present. This presence, this personal manner, does not exist with any other artist.

If neither in the text nor in the music, the essential essence and specialness of Dylan’s art can be found but rather in his emotional drive, how could I go about attempting German versions of it? – It came about by itself at the very beginning that I simply had to remain close to the original. I love these songs like they are and want to leave them as they are. There were no “wandering desires”.

*

It’s legitimate and often very useful, if rock music is also entertainment art. If the said presence, however, exceeds this, it can have as its cause the fact that an artist is simply more intelligent and sensitive than others and that art is a means for him for achieving a greater presence, that he accomplishes through art a greater self-perception and self-acknowledgement. What would be the case, if this person would first be present, whereby he first and foremost functions as an artist by writing songs, in order to gain this presence at all?

Maybe the gigantic Dylanesque Oeuvre lies in a corresponding compulsion (which then would also concern the fans, too). Dylan is endlessly on tour and he has written hundreds of songs, of which many have not even been released.

*

In 1966, Bob Dylan was nearly killed in a motorcycle accident: a traumatic experience, which certainly threw him back to the core of his personality. In his recovery period, Dylan invited the musicians of The Band to him and songs originated in the basement of his house, which some fans regard as some of his most significant works; these were recorded on Basement Tapes (the originals, by the way, landed, curiously, in the archive of Neil Young) and later (1975) were released as such. One song was deleted and remained unpublished for years and became a secret tip, and that was the song with the title I’m Not There.

This song occupies a very special place in Dylan’s work; indeed, it is a key song. Four chords are the basis for a kind of improvisation, which ends in a single notation, namely this single repeating refrain: “I’m not there.” The text appears to be not only improvised but is in many places simply not understandable. Dylan uses a private language and seems to take no great concern for usual word meanings – everything flows directly from his feelings and from his subconscious. Cognitive meaning is hardly of any significance next to the conquest of presence; he will later say in the song Standing in the Doorway: “I see nothing to be gained by explanation”. I’m not There is a direct expression of his inner self.

Out of the non-existence Dylan seems – so one takes it from his

improvisation – to have made some mistakes in life which he regrets. Now he accomplishes presence by taking action against his non-presence. He never does this so clearly again, even though the motor of his art – as already mentioned – remains self-verification.

For Dylan there is only one thing: to be myself. The problem is only: Who am I? – He is not himself at all or is just not there! Of the many sayings which are passed on by Dylan, one runs: “All that I can do is to just be myself – whatever that may be.” The greatest accomplishment and that which so distinguishes him from other artists, is that he prefers to simultaneously abandon his work if he is not himself rather than be a pseudo-person. He would rather ruthlessly maintain the disastrous current condition: “But with the truth so far off, what good will it do?” (Joker Man)

Nowhere else does this stand out so clearly as in his magnificent album Time Out of Mind from the year 1997. While heavenly hosts of artists (and just people in general) lead the way and delude themselves with something and cannot appease the great distress resulting from Non-existence, Dylan sings in Trying to get to Heaven: “They tell me everything is gonna be all right, but I don’t know what ‘all right’ even means.” He rejects this false comforting. It is not Dylan’s desire to be “all right” but to be himself – in whatever condition albeit, and even if that is Anti-life.

This album Time Out of Mind constitutes an anti-album, which consists of anti-songs, in which anti-texts only reflect anti-existence. The tenor is: everything is just detachment from life. Music and text float the whole time above reality and look down upon it with longing. It is a departure from life and remains until today his legacy.

*

Twelve years after the recordings in the basement (in the year 1979 to be exact) the yearning again grows – the biographical context is important but must not be here examined – for introspection through revelation. The announced Changing of the Guard takes place following Street Legal, and three “Christian” albums are produced: a new “way of thinking” with a “different set of rules”. Here, especially in Saved, Dylan’s feelings speak as the basis of his existence, more clearly than in his entire career; no place else does he express his love so intensely as here, nowhere else in his art than here does he come so close to the feeling “to be there”.

*

It’s easy to see why I am fascinated to this degree with Dylan and where the commonalities between artist and recipient lie. It is obvious that it can’t result in such artistic experiences, like I had from hearing Saved and other Dylan records, if the recipient is not similarly emotionally constituted as the artist. To put it straight, this constitution reads: I am not there, or rather – in the feelings of love then –: Finally I am there.

What could have been of more concern to me than to also cover the song I’m Not There? That was not quite possible for me, but as something corresponding to this, a project could be devised which of course could exceed this and in many aspects reflects a reform and a radical reversion to one’s own – in the geo-cultural as well as the personal sense. This project bears the working title I am not there / I am there and will consist of a series of musical dramatic pieces called Post Passions through which the protagonist – it is the so-called Truth-Teller – at any rate, improvises.

These Post Passions show a similarity with Dylan’s I’m not there, whereby the complaint “I am not there” quite regularly repeats, like in repeating refrains – but also much like John Lennon’s songs Mother and Cold Turkey, where likewise improvisations take place. And thus the improvisation consists therein that the protagonist in his distress simply states his entire truth without any inhibition or constraint and – going far below the verbal – expresses this sufficiently.

*

After the apocalyptic collapse of the United States, the end of the pax Americana and that which the faithful regard as the appearance of the Anti-Christ, an additional changing of the guard will force itself in a fundamental cultural change similar to a loving devotion or characterizing a return to the truth; not in any sort of ideological, religious or scientific but in a purely personal sense. A consciousness that shatters.

On this Journey through Dark Heat, Dylan leads the way: “The truth was obscure, too profound and too pure. To live it you have to explode.”

Peter Post, 2015